HISTORY OF COLLIER HILLS HOUSING DEVELOPMENT

It is odd now to think of Collier Hills as a suburb of Atlanta, but when it was first developed, it was just that. Modern history starts in 1825 when the state of Georgia took land from the Creek Indians for a land grant. Just a few years later, in 1831, it was sold to Meredith Collier. It remained intact and in the Collier family until 1925, when a section near the corner of Peachtree and Collier Road was developed. With the Great Depression, however, growth stopped.

Development restarted in 1937, with a few houses being built along Collier Road in the late 1930s. Then, major development occurred in 1940-41 in the northeast corner of the neighborhood on Dellwood, Redland, and Golfview (now Collier Hills North), as well as in the southwest corner on Echota (now Collier Hills). These homes are of the type called American Small House and were built by Herbert W. Nicholes. While the interiors are similar, the builder gave them unique facades that consist of a mix of single story Roman and Georgian column styles.

When the United States entered World War II, construction once again fizzled out. When it started back up in the late 1940s, the remaining lots from Echota to Collier Road were completed, and the style of the homes changed. The later ones are considerably larger than the ones built in 1940, and the columns no longer were used on the front facade. While many homes have since been expanded, often this has been done in a way that does not substantially change the look from the front - by expanding to the back or by using the attic space.

Also significant to the livability of the neighborhood is that in 1938, the Collier estate deeded land to the city for use as a park. It consists of the strip of land on the east side of Tanyard Creek from the Bobby Jones golf course to Collier Road and then continuing southward on both sides of Tanyard Creek from Collier Road to the railroad. In 2007, the land between Bobby Jones golf course and Collier Road on the west side of Tanyard Creek was deeded to the city and became Louise G. Howard Park. These park spaces make the neighborhood a special place with playgrounds, a walking path, and a large field for recreation within walking distance of many homes. Surrounding Tanyard Creek Park and Louise G. Howard Park as well as being bounded by Atlanta Memorial Park and Bobby Jones Golf Course on the north makes this a truly unique neighborhood: single family homes near downtown, with plenty of open space, and containing houses with a unique look and character.

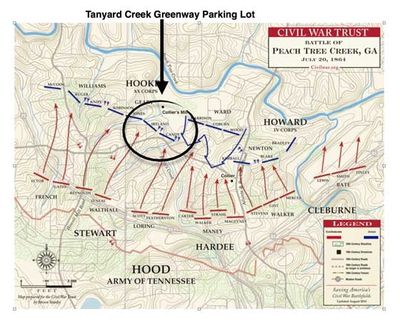

This area is also rich in Civil War history. Tanyard Creek Park was at the center of the Battle of Peachtree Creek, which was fought on July 20, 1864 and was the site of some of the bloodiest fighting of the Civil War. Along Collier Road and Bobby Jones Golf Course, there are several historical markers describing the battle. (more history below)

Sources:

1 “Collier Property Held for 106 Years” The Atlanta Constitution, Aug 15, 1937, pg. 2K

2 “New Club Planned for City Golfers at $250,000 Cost” The Atlanta Constitution, Sep 2, 1928, pg. 1A

3 “New Paradise for Golfing Fraternity Planned by Prominent Atlanta Men” The Atlanta Constitution, SEp 2, 1928, pg. 8A

4 http://atlmemorialpark.org/history/ quoting Atlanta Constitution November 1938

Mill wheels from Collier Mill which was situated on Tanyard Creek just downstream of Collier Road

Sources

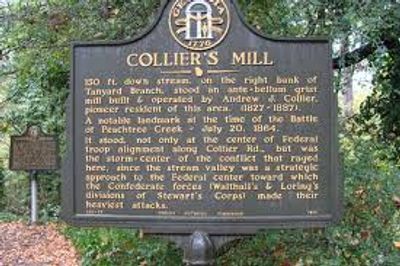

COLLIER'S MILL

Collier's Mill was located near the current Redland Road entrance to the neighborhood.. If you look closely, you can see ruins of the foundation near the creek bank just downstream of the bridge.

THE BATTLE OF OF PEACHTREE CREEK

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Peachtree_Creek

Throughout the morning of July 20, the Army of the Cumberland crossed Peachtree Creek and began taking up defensive positions. The XIV Corps, commanded by Major General John M. Palmer, took position on the right. The XX Corps, commanded by Major General Joseph Hooker (the former commander of the Army of the Potomac who had lost the Battle of Chancellorsville) took position in the center. The left was held by a single division (John Newton's) of the IV Corps, as the rest of that corps had been sent to reinforce Schofield and McPherson on the east side of Atlanta. The Union forces began preparing defensive positions, but had only partially completed them by the time the Confederate attack began.[8]

The few hours between the Union crossing and their completion of defensive earthworks were a moment of opportunity for the Confederates. Hood committed two of his three corps to the attack: Hardee's corps would attack on the right, while the corps of General Stewart would attack on the left as the corps of General Benjamin Cheatham would keep an eye on the Union forces to the east of Atlanta.

Hood had wanted the attack launched at one o'clock, but confusion and miscommunication between Hardee and Hood prevented this from happening. Hood instructed Hardee to ensure that his right flank maintained contact with Cheatham's corps, but Cheatham began moving his forces slightly eastward. Hardee too began side-stepping to the east to maintain contact with Cheatham, while Stewart began sliding eastward as well in order to maintain contact with Hardee. It was not until three o'clock that this movement ceased.[9]

The battle as seen from General Hooker's position

The Confederate attack was finally mounted at around four o’clock in the afternoon. On the Confederate right, Hardee's men ran into fierce opposition and were unable to make much headway, with the Southerners suffering heavy losses. The failure of the attack was largely due to faulty execution and a lack of pre-battle reconnaissance.

On the Confederate left, Stewart's attack was more successful. Two Union brigades were forced to retreat, and most of the 33rd New Jersey Infantry Regiment (along with its battle flag) were captured by the Rebels, as was a 4-gun Union artillery battery. Union forces counterattacked and after a bloody struggle, successfully blunted the Confederate offensive. Artillery helped stop the Confederate attack on Thomas' left flank.

A few hours into the battle, Hardee was preparing to send in his reserve, the division of General Patrick Cleburne, which he hoped would get the attack moving again and allow him to break through the Union lines. An urgent message from Hood, however, forced him to cancel the attack and dispatch Cleburne to reinforce Cheatham, who was being threatened by a Union attack and in need of reinforcements.

The Union lines had bent but not broken under the weight of the Confederate attack, and by the end of the day the Rebels had failed to break through anywhere along the line. Hood withdrew into defenses of Atlanta the following day, 21 July.[4]Estimated casualties were 4,250 in total: 1,750 on the Union side, including McPherson, and at least 2,500 on the Confederate.[2]

Union graves close to Peachtree Creek

Neighbors still find civil war artifacts in their yards.